While living in London in the late 1980s, producer Laura Bickford happened on a Channel 4 mini-series entitled "Traffik," which tracked a drug route from Pakistan through Europe to Great Britain. Bickford recalls, "The story stayed with me. When I moved back to the United States, I began to notice that, several times a week, newspapers were reporting on drug trafficking. There were social issue stories, stories about law enforcement, and stories about prisons and drugs. I was astonished that you could read all about the price of drugs going up or down, and who controlled the cartels. It seemed that, although an illegal enterprise, the entire business of it was common knowledge. I kept thinking of 'Traffik' and the impression it had made on me, and I started to clip articles on anything to do with illegal drugs and the drug trade. Finally, I tracked down the agents for the miniseries and optioned the remake rights for an American feature film version."

While living in London in the late 1980s, producer Laura Bickford happened on a Channel 4 mini-series entitled "Traffik," which tracked a drug route from Pakistan through Europe to Great Britain. Bickford recalls, "The story stayed with me. When I moved back to the United States, I began to notice that, several times a week, newspapers were reporting on drug trafficking. There were social issue stories, stories about law enforcement, and stories about prisons and drugs. I was astonished that you could read all about the price of drugs going up or down, and who controlled the cartels. It seemed that, although an illegal enterprise, the entire business of it was common knowledge. I kept thinking of 'Traffik' and the impression it had made on me, and I started to clip articles on anything to do with illegal drugs and the drug trade. Finally, I tracked down the agents for the miniseries and optioned the remake rights for an American feature film version."

"Once I had optioned the miniseries, I went to Steven Soderbergh with my research and we talked about his directing the movie. I thought he would be the perfect director for the project because he's been interested in telling intertwining stories, stories with different time frames. The miniseries had three overlapping stories which affected how you understood the whole issue. I thought such a structure would suit Steven."

Soderbergh allows, "This was a subject that I'd been interested in for a while, but I wasn't sure what form it should take. I never wanted to make a movie about addicts, and when Laura came to me about 'Traffik,' which I had seen some years before, I thought it had a shape that I could work with."

"Drugs are one of the key social issues in our culture today: everyone knows someone who has been touched by it, whether it's a friend or a family member. I feel like it's in the air right now and people are talking about it a lot."

"Drugs are one of the key social issues in our culture today: everyone knows someone who has been touched by it, whether it's a friend or a family member. I feel like it's in the air right now and people are talking about it a lot."

"What we had liked about 'Traffik' was the intersecting stories," adds Bickford. "There was no individual bad guy; the bad guy was the system. What we wanted to take from the miniseries was the intersecting storylines of different people caught up in this web, and to do it in the policier genre."

The next step in the process was to find a screenwriter. Both Bickford and Soderbergh had read an unrelated script that they liked, written by Stephen Gaghan. When they contacted Gaghan they discovered, to their surprise, that the screenwriter had already committed to write a script about drug trafficking for producers Edward Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz.

The next step in the process was to find a screenwriter. Both Bickford and Soderbergh had read an unrelated script that they liked, written by Stephen Gaghan. When they contacted Gaghan they discovered, to their surprise, that the screenwriter had already committed to write a script about drug trafficking for producers Edward Zwick and Marshall Herskovitz.

Herskovitz remembers, "The genesis of this script defines the word 'serendipity.' For a long time, Ed had wanted to do a film about the drug wars: the hypocrisies, the difficulty, the craziness. He'd been working with Stephen Gaghan on a story which had several different focuses on the drug wars."

Zwick elaborates, "Several years ago I read an article about a conflict in which three competing law enforcement agencies ended up in a running gun battle - an extraordinary moment of absurdity. Then I read a book by a former professor who had lived in the pristine and removed academic world and who was appointed by the President to high office. In this book, he talks about going into government as if through the looking glass and describing what it is like from the inside: its contradictions, its challenges, and its absurdities. There was something about these two stories that intrigued me, and I began to work with Steve Gaghan to develop a screenplay."

Gaghan recalls, "I went all over the country to research the story. In Washington, D.C., meeting with the policymakers - the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the head of the Association of Police Chiefs, the DEA, members of think tanks from the right and the left, journalists at The Washington Post and The New York Times - and I met many smart, committed people with passionate opinions. People who have essentially dedicated their lives to keeping children off drugs. These were people with multiple graduate degrees who were working in public service for their country, for the American people."

Gaghan recalls, "I went all over the country to research the story. In Washington, D.C., meeting with the policymakers - the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the head of the Association of Police Chiefs, the DEA, members of think tanks from the right and the left, journalists at The Washington Post and The New York Times - and I met many smart, committed people with passionate opinions. People who have essentially dedicated their lives to keeping children off drugs. These were people with multiple graduate degrees who were working in public service for their country, for the American people."

"I had notebook after notebook of incredible quotes, and what I came away with first and foremost was a sense of despair. Speaking candidly, nobody believed the current policies were working - nobody. The information cut across the political spectrum, which was interesting. It fascinated me that there wasn't an easy answer to the problem."

The upshot was that rather than have two competing projects, Zwick and Herskovitz partnered with Bickford to produce Traffic, with Soderbergh directing from a screenplay by Gaghan.

The upshot was that rather than have two competing projects, Zwick and Herskovitz partnered with Bickford to produce Traffic, with Soderbergh directing from a screenplay by Gaghan.

Zwick notes, "I had always admired Steven's films. When we met, it was an easy decision to partner on this particular project. In the end, the movie contains elements of the story that I was working on and elements of the story that Steven and Laura were working on."

Bickford adds, "One of the major decisions we had to make was whether we'd do America and Colombia, or America and Mexico. We decided to do Mexico because we wanted something fresh and we felt we'd all seen movies about Colombian drug lords. Also, Mexico's rise in the drug trade has only happened in the last 10 years. It used to be that they were just the transporters but after the United States clamped down on Escobar and the cartels in Colombia were dispersed, the Mexican cartels gained more power. Now, rather than just being paid a fee to transport drugs, they take a piece of the action. There's a lot more money at stake and it has begun to affect every aspect of Mexican society: their judicial system, their police force, and the entire fabric of the country."

"There were so many different stories that could go into the American version that picking which ones to do was really tough. The hardest part was to streamline it. We sifted through all the stories and decided which issues were most important. During the years I had been doing research for the story, I had probably cut out 300 articles from different sources. I had also met Tim Golden, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on drug trafficking and knew many of the people on either side of the border who were involved in the war on drugs. We hired Tim to be the film's story consultant."

"There were so many different stories that could go into the American version that picking which ones to do was really tough. The hardest part was to streamline it. We sifted through all the stories and decided which issues were most important. During the years I had been doing research for the story, I had probably cut out 300 articles from different sources. I had also met Tim Golden, who had won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on drug trafficking and knew many of the people on either side of the border who were involved in the war on drugs. We hired Tim to be the film's story consultant."

Soderbergh comments, "The development of the script was very gradual and complicated because the three stories are very dense. There is a new headline every day about the drug war and you'd find yourself wanting to pull in some of those new elements. We were constantly updating and revising. I remember while being in production on 'The Limey,' I was having phone discussions with Stephen Gaghan about what elements we wanted to include. In borrowing the structure from the British miniseries we had to completely create one of the stories, because one of theirs didn't work when transplanted to the United States."

Zwick, adds, "It was one of those amazing circumstances when you find yourself trumped by the headlines. You think you've invented something and then you'd find something even far more outrageous happening in life. I think what we finally ended up with is a kind of mosaic. Looking at any one piece, however compelling, doesn't really give you the resonance that the whole has. In this case, it's a topic that's riddled with contradictions. I'm as interested in the contradictions as I am in the polemics of it. I think you really needed to have different strands vibrating off each other in order to get the whole portrait."

Zwick, adds, "It was one of those amazing circumstances when you find yourself trumped by the headlines. You think you've invented something and then you'd find something even far more outrageous happening in life. I think what we finally ended up with is a kind of mosaic. Looking at any one piece, however compelling, doesn't really give you the resonance that the whole has. In this case, it's a topic that's riddled with contradictions. I'm as interested in the contradictions as I am in the polemics of it. I think you really needed to have different strands vibrating off each other in order to get the whole portrait."

Bickford recalls that "at a certain point Steven Soderbergh, Stephen Gaghan, Tim Golden and I made a research trip to San Diego and Mexico, where we met many of the real people involved in the war on drugs. We were given a lot of very good information and detail from them which was later reflected in the script."

"We spent a lot of time talking about the Mexico section of the story," explains Soderbergh. "I remember sitting in my living room with Stephen Gaghan and a set of colored index cards, mapping out scene by scene the structure for the entire film. While I went off to shoot Erin Brockovich (2000), he wrote the first draft of the screenplay."

Recalling the experience of working with Soderbergh, Gaghan says, "Steven really does help you find your best work. Before I started on the first draft, we talked through all aspects of the film and worked on all the story lines together. From the very beginning, he had such an incredible sense of the shape of the film. He saw all the pieces in his head, how they fit together. He understood exactly the people I had invented. Steven has the subtlest insights into human nature and knows how to get the best out of people."

"The character of Javier Rodriguez portrayed in Traffic by Benicio Del Toro] came out of discussions I had with Steven. Every day in the newspaper, there were fascinating stories about border politics. I was reading a lot about the effect of American drug policy on Mexico, and Tim Golden suggested that we show what the day-to-day is like for Tijuana lawmen and citizens. The vast American appetite for drugs and the current interdiction strategy have destroyed the Mexican towns along the border with the United States."

"The character of Javier Rodriguez portrayed in Traffic by Benicio Del Toro] came out of discussions I had with Steven. Every day in the newspaper, there were fascinating stories about border politics. I was reading a lot about the effect of American drug policy on Mexico, and Tim Golden suggested that we show what the day-to-day is like for Tijuana lawmen and citizens. The vast American appetite for drugs and the current interdiction strategy have destroyed the Mexican towns along the border with the United States."

Zwick says, "Stephen Gaghan was uniquely suited to write this screenplay because he has great political savvy. With his background as a journalist, he was extraordinarily assiduous about the research: he went on an odyssey which took him to many places, to many experts, and into various law enforcement bureaus. I think it wasn't for nothing that independently Steven, Laura, and I chose him to write the screenplay."

Herskovitz adds, "Another wonderful quality about Stephen Gaghan is his ability to express the voices of so many different aspects of society. When you read the script and then see the film, the voice of Washington sounds real, the voice of the drug lords sounds real, the voice of the Mexican police sounds real, the voice of the teenagers sounds real. He goes to every level of society in two countries, and it all has the ring of truth."

"I think that Steven Soderbergh has tried to further that aspect. Much of the picture has been shot with a hand-held camera which Steven himself operated. As you watch, there is a quality of a reality being captured. It's more dynamic than a documentary, more dramatic."

"The war on drugs takes place in many different countries at many different levels with varying degrees of success, or lack of success," declares Herskovitz. "Traffic tries to give a sense of the craziness of all of that, as well as the human drama - and, in odd moments, the comedy - of it, because there are those perverse juxtapositions in the war on drugs. The movie tries to be very honest, as well as entertaining, about how difficult it is to pursue a war on drugs when millions and millions of people in this country are using drugs. We're talking about every aspect of society: middle-class, wealthy, men, women, children, professionals. There is an enormous demand for drugs in this society, and until we deal with that demand and why it exists and the psychological issues and issues of rehabilitation, we are never going to make a dent in this war."

Soderbergh concludes, "The idea is to suggest the larger picture by focusing in great detail on a small aspect of that picture. If we've done our jobs right on Traffic, everybody will be pissed off. The decriminalization people will think that we were not proposing their point of view; the hard-core, lock 'em-up-and-throw-away-the-key people will think we're being too soft. It would be great if everybody comes away thinking that we took the other side's approach. We're trying to be as dispassionate as we can, just show you a snapshot and say, 'This is what's happening now.'"

"Our cast came together in various ways and is a combination of people we had in mind from the beginning and actors who were interested because they'd heard about the movie," says Soderbergh. "At the end of the day, you get the cast you're supposed to get. Aside from the primary leads, the film has an enormous range of characters - over 110 speaking parts. It adds up when you have that many characters on screen. Any film is only as good as every day player in it. You have to make sure that those actors are great too. It's crucial that they all register with the audience."

"Our cast came together in various ways and is a combination of people we had in mind from the beginning and actors who were interested because they'd heard about the movie," says Soderbergh. "At the end of the day, you get the cast you're supposed to get. Aside from the primary leads, the film has an enormous range of characters - over 110 speaking parts. It adds up when you have that many characters on screen. Any film is only as good as every day player in it. You have to make sure that those actors are great too. It's crucial that they all register with the audience."

"One of the benefits about having a piece of material that's actor-friendly is that you can get good people to come in. There are a lot of people in Traffic who I've always liked and wanted to work with and this was an opportunity to do so. Also, I have this tendency to use people again and again, so expanding the repertory is beneficial for me as a filmmaker!"

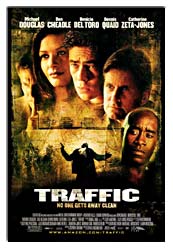

"Catherine Zeta Jones, Michael Douglas, and Benicio Del Toro were the first three people we asked to be in the movie. Luckily enough, they all came on board," reveals Bickford.

"Catherine Zeta Jones, Michael Douglas, and Benicio Del Toro were the first three people we asked to be in the movie. Luckily enough, they all came on board," reveals Bickford.

One story in Traffic centers on Tijuana State policeman Javier Rodriguez, portrayed by Benicio Del Toro.

Bickford states, "One thing that we wanted to make clear is that all the Mexicans aren't 'bad guys.' Benicio's character, Javier, is a good man caught in a bad world where he might not have a choice. The 'bad guy' is the system and the corruption around the illegal drug trade. Javier has to make a decision how to deal with it: does he take bribes and essentially work for the cartels or not? It's almost impossible for him, at some point, to not work with one side or the other. So we tried to show what it's like for a police officer who's totally honest, but has no way to survive without making some compromises."

"One of the things I've always admired about Steven's directing is that he is really concerned with making things truthful and real and entertaining at the same time," adds Bickford. In keeping with this way of working, Soderbergh elected to film all the scenes in which Mexican characters speak with one another in Spanish.

"One of the things I've always admired about Steven's directing is that he is really concerned with making things truthful and real and entertaining at the same time," adds Bickford. In keeping with this way of working, Soderbergh elected to film all the scenes in which Mexican characters speak with one another in Spanish.

Soderbergh explains, "It was always envisioned that the scenes in which Mexicans are speaking to Mexicans would be done in Spanish. I felt that if you wanted anybody to take the film seriously on any level, we had to do that. Within the film there is an important distinction between how Mexicans speak to one another and how they speak to Americans. Even within the Spanish language, it's a completely different way of speaking. Their use of metaphor is completely different when they talk to each other and when they speak in English to an American. I wanted people to understand that, because impenetrability of another culture is a part of the Mexican story."

"You have Americans coming into Mexico and making a lot of assumptions about rules they can impose on the Mexican culture. And it simply doesn't work that way. So, having the dialogue spoken in Spanish seemed like the way to make audiences buy it and believe it. It makes those scenes much more compelling because you really feel it's happening in front of you. It isn't just a Spanish person speaking English with a Spanish accent."

"You have Americans coming into Mexico and making a lot of assumptions about rules they can impose on the Mexican culture. And it simply doesn't work that way. So, having the dialogue spoken in Spanish seemed like the way to make audiences buy it and believe it. It makes those scenes much more compelling because you really feel it's happening in front of you. It isn't just a Spanish person speaking English with a Spanish accent."

Further contributing to the authenticity of Traffic was Soderbergh's decision to cast a number of Latino actors in key roles. The cast includes Puerto Rican-born Benicio Del Toro and Luis Guzman; Cuban-born Steven Bauer and Tomas Milian; and Mexican-born Jacob Vargas and Marisol Padilla Sanchez.

Benicio Del Toro found, as did other cast members, this emphasis on ethnic authenticity to be refreshing: "Steven's idea, to do it in Spanish - it was exciting to tackle that. It adds texture to the story, realism of a kind we haven't seen."

Del Toro, who first captured critical attention as Fred Fenster in Usual Suspects, The (1995), says that his character of Javier Rodriguez "is the underdog, the guy who's trying to do the right thing. But the evils and the potential for corruption might be stronger than him."

"His relationship with Manolo played by Jacob Vargas is like a big brother/younger brother one. Then it gets complicated because of drugs and money. Javier's conflict is whether to sell out his integrity. If he doesn't, it could cost him his life."

"His relationship with Manolo played by Jacob Vargas is like a big brother/younger brother one. Then it gets complicated because of drugs and money. Javier's conflict is whether to sell out his integrity. If he doesn't, it could cost him his life."

For Del Toro, his character's feeling about the U.S. "is that the money for drugs is coming from there, the demand for drugs is coming from there, but the actual drugs are coming through his country. At the same time, the DEA is trying to do the right thing."

Gaghan relates, "One of the people I met who was well-informed about our national drug control policy told me, when I asked him about corruption in Mexico, 'In America we're lucky because most people who go into law enforcement don't view it as an entrepreneurial activity, whereas in Mexico it's the polar opposite.'"

"I love the way Javier's story ends, and Benicio helped us find that ending. It's realistic and incredibly poignant. Your choice as a Mexican police officer is simple - gold or lead. You take the money from the drug dealers or you're found dead in a ditch."

Another section of Traffic focuses on Robert Wakefield, the U.S. President's newly appointed drug czar (played by Michael Douglas).

"Robert Wakefield is a conservative Ohio State Supreme Court Judge and a very bright and savvy guy," explains Soderbergh. "But while he is navigating his way through the Washington, D.C. political scene, unbeknownst to him, his teenage daughter Caroline played by Erika Christensen] has developed a drug problem - one which, like most parents, he at first believes is not severe, but which turns out to be extremely severe. The acknowledgment of her addiction forces him to confront, on a very personal level, the problem he's supposed to be fighting on a national level."

"Robert Wakefield is a conservative Ohio State Supreme Court Judge and a very bright and savvy guy," explains Soderbergh. "But while he is navigating his way through the Washington, D.C. political scene, unbeknownst to him, his teenage daughter Caroline played by Erika Christensen] has developed a drug problem - one which, like most parents, he at first believes is not severe, but which turns out to be extremely severe. The acknowledgment of her addiction forces him to confront, on a very personal level, the problem he's supposed to be fighting on a national level."

About the Wakefields, Gaghan says, "I love the silences in the Wakefield house, the things that are unspoken between them as they try to deal with this problem for which there is no easy answer. When I watched Michael Douglas, Amy Irving cast as Robert Wakefield's wife Barbara, and Erika Christensen inhabit these roles, it took about a second for me to realize, 'Oh, of course, there it is.'"

Michael Douglas acknowledges, "I always go for a movie with a good, plot-driven story. This film has three exciting stories that are woven together and deal with the theme of drugs. But it's the emotional impact that makes the picture exciting. The interesting thing about this film is that I only really knew about my own section. There are two other stories, one with Benicio Del Toro and one with Catherine Zeta Jones, and I only had little whiffs of those."

"Of the film's three sections, mine is about my character dealing with the reality of the problem he's having with his daughter vs. his image in the community. It's the classic situation of, 'It can never happen to you, it only happens to other families.' Robert Wakefield's 16-year-old daughter is very quickly spinning out of control at the same time that he's about to get his Presidential appointment."

Douglas notes, "I didn't have to do a lot of research for this role because to a certain degree, my character, other than handling drug cases as a jurist, doesn't have a great deal of knowledge about the problem. He's not supposed to be an expert on the subject. The part required a certain amount of innocence: my character has people educating him and talking to him on the subject. This way the audience sees, through Robert Wakefield's eyes, the enormous scope of the problem."

Douglas notes, "I didn't have to do a lot of research for this role because to a certain degree, my character, other than handling drug cases as a jurist, doesn't have a great deal of knowledge about the problem. He's not supposed to be an expert on the subject. The part required a certain amount of innocence: my character has people educating him and talking to him on the subject. This way the audience sees, through Robert Wakefield's eyes, the enormous scope of the problem."

"We filmed a scene at the San Ysidro / Tijuana border in San Diego. When you see 28 lanes of traffic coming through, you begin to get a perspective of how overwhelming this issue is. It's so sophisticated that there are lookouts on the Mexican side watching the border through binoculars. They know which dogs are good at their job and which ones have been burnt out due to the constant smelling. The dogs' cycles are very short in terms of being 'sniffers'; the lookouts will call and tell traffickers to change lanes based upon which dogs are working. You get a sense of the enormity of the problem, of looking for a needle in a haystack."

Douglas says, "If you look at the drug problem as being a tripod, the three legs are police enforcement, education, and rehabilitation. For a long time, our government was much more into police enforcement. Now they realize that they have reached the point of being so overwhelmed that they have to rely much more on education and rehabilitation - and there are a lot of arguments between education and rehabilitation. In other words, you can educate children up to a certain age, and then do you rehabilitate them or do you bring in law enforcement? My character's outlook changes as he is affected in his personal life."

Douglas says, "If you look at the drug problem as being a tripod, the three legs are police enforcement, education, and rehabilitation. For a long time, our government was much more into police enforcement. Now they realize that they have reached the point of being so overwhelmed that they have to rely much more on education and rehabilitation - and there are a lot of arguments between education and rehabilitation. In other words, you can educate children up to a certain age, and then do you rehabilitate them or do you bring in law enforcement? My character's outlook changes as he is affected in his personal life."

Amy Irving comments, "The Wakefields, a fairly typical family, are confronted with the hard fact of their daughter having become a drug addict. It's a different world today than in the 1960s, when drugs were recreational. My character experimented with drugs in college and was a bit of a radical. Like all good radicals, she grew up and now works within the system."

"Adults who grew up in the '60s and experimented with and experienced drugs might be more lenient and less fearful because they have personal knowledge and familiarity with the subject. What's dangerous today is that the drugs are much stronger, there's no control, and it's no longer just a recreation. It's a very dangerous business now, and the people selling drugs are targeting kids. This film shows how, on all the levels, drugs are affecting our world, our children, families, politics - everything. I don't think there's anybody who doesn't know someone who hasn't faced the drug dilemma in one way or another."

"Adults who grew up in the '60s and experimented with and experienced drugs might be more lenient and less fearful because they have personal knowledge and familiarity with the subject. What's dangerous today is that the drugs are much stronger, there's no control, and it's no longer just a recreation. It's a very dangerous business now, and the people selling drugs are targeting kids. This film shows how, on all the levels, drugs are affecting our world, our children, families, politics - everything. I don't think there's anybody who doesn't know someone who hasn't faced the drug dilemma in one way or another."

Irving reveals, "I have somebody very close to me who has dealt with a daughter on drugs, and another friend whose daughter spent a night in prison. She told me that if her daughter came out and had an arrogant attitude towards her, then she would feel that her daughter was lost to her. But if she came out and she cried, then she knew she hadn't lost her yet. I have a scene where my character's daughter comes out after spending the night in a juvenile detention center. I was able to call on my friend's first-hand experience for that scene."

"What makes Traffic compelling is that you are always in suspense as far as what's going to happen to the characters. It deals with so many different levels of humanity, and the entertainment value is in the storytelling and the punch-in-the-gut of how real it is. I think that besides having been told a good story, the audience will walk away with a broader awareness of the world and what we're up against - and maybe pay more attention to what our children are doing and not take it casually."

Screenwriter Gaghan, who grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, says, "To the bored kids in the Midwest, drugs and alcohol are a way to have a little adventure. You can pick up a 6-pack, go out, and have an adventure with little consequence. But for that under 10 % of the population that has addictive personalities, it has a different level of risk. And these people will turn into tragedies: they throw away their lives, ending up living in jail, institutions, or dead. Or they'll quit and get sober. There's no in-between."

Screenwriter Gaghan, who grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, says, "To the bored kids in the Midwest, drugs and alcohol are a way to have a little adventure. You can pick up a 6-pack, go out, and have an adventure with little consequence. But for that under 10 % of the population that has addictive personalities, it has a different level of risk. And these people will turn into tragedies: they throw away their lives, ending up living in jail, institutions, or dead. Or they'll quit and get sober. There's no in-between."

Relative screen newcomer Erika Christensen won the coveted role of Caroline Wakefield, the A-plus high school student living with her parents in an affluent Cincinnati suburb, whose spiral into drug abuse causes her family to rethink their priorities. While at first drugs are a weekend and after-school recreation for her, Caroline's eventual addiction takes her from the manicured neighborhood of her parents' Hyde Park home to the streets and alleys of Cincinnati's inner city, where drugs of all kinds are readily available - for a price.

Christensen states, "For me, the script was very powerful because it showed the scope of the drug problem and how it's not limited to a certain social strata. My character is a straight A student, a National Merit Finalist - and a coke and heroin addict. It's a good demonstration of how addiction can happen to anyone if they don't take responsibility for their own life."

She prepared for the role by "attending AA meetings and talking to ex-addicts and people who were coming through their addiction. The ex-addicts explained the mentality of an addict to me, how getting drugs becomes the only thing that matters in life. Nothing else is important - morality goes out the window. What was amazing was how eloquent these people are. I also spoke with the president of a rehabilitation and education center. I learned a lot from him, especially about what happens physically to people addicted to drugs."

"One of the things I learned from my research is that more education is needed, particularly as it applies to teenagers. Kids need to be told something more than just 'drugs are bad.' They need to see the whole picture - what happens to your body and your mind. As a preventative action, I think education should be a huge factor. It seems to make sense to try to stop the users before they begin."

Playing opposite two very experienced actors as Caroline's parents, the 18-year-old Christensen found it "great to be working with Michael Douglas and Amy Irving. I like to watch different people and see how they work, how they produce these wonderful scenes, and I learned a lot just from watching Amy and Michael. When they say the words, it sounds so natural, just as I'm sure Stephen Gaghan wanted them to sound."

Playing opposite two very experienced actors as Caroline's parents, the 18-year-old Christensen found it "great to be working with Michael Douglas and Amy Irving. I like to watch different people and see how they work, how they produce these wonderful scenes, and I learned a lot just from watching Amy and Michael. When they say the words, it sounds so natural, just as I'm sure Stephen Gaghan wanted them to sound."

Christensen played many of her other scenes opposite Topher Grace, cast as the boyfriend who introduces Caroline to freebasing cocaine. "Topher and I had an instant connection," Christensen recalls. "We were really comfortable with one another. Our characters have this chemistry and really understand one another, and we didn't have to pretend. Some of the drug scenes could have been uncomfortable, but they never were: we are so completely not the characters that we're playing."

Describing the character of Seth Abrahms, screenwriter Gaghan says, "Seth is very bright, perhaps too bright. He seems to be able to dabble in drugs and still do well in school. He has very well-informed opinions yet he has no conception of the level of destruction in his friend's life and he's blasé about it. I think there are people who have had friends who've just disappeared down ratholes, whose lives have been thrown away, and they didn't truly perceive it. It's an interesting dynamic."

Describing the character of Seth Abrahms, screenwriter Gaghan says, "Seth is very bright, perhaps too bright. He seems to be able to dabble in drugs and still do well in school. He has very well-informed opinions yet he has no conception of the level of destruction in his friend's life and he's blasé about it. I think there are people who have had friends who've just disappeared down ratholes, whose lives have been thrown away, and they didn't truly perceive it. It's an interesting dynamic."

Topher Grace adds, "Seth thinks he's the brightest person in the room - and maybe he is. He's very cocky for a 17-year-old and can be a real jerk - and not just because he leads Caroline into a life of substance abuse. He's young and still vulnerable and he really likes Caroline. He's trying to impress her so, in his head, the motivation for introducing Caroline to freebasing is okay. Because he can do drugs on a take-it-or-leave-it basis, it never occurs to him that the same might not be true for her."

Grace reports, "The scenes where we were supposed to be high - which were most of my scenes - took a lot of physical preparation. First they'd put on a kind of 'whitening' makeup and then red, bleary stuff under our eyes and our noses. Then they'd blow this kind of mint dust into our eyes to make them water. It was terrible."

But some of Grace's most difficult scenes were dialogue-driven ones opposite Michael Douglas, whose character holds Seth accountable for Caroline's addiction. "This is my first film, so you can imagine how nervous I was to be doing scenes with Michael. I can call him 'Michael' now because I've worked with him," laughs Grace. "I can't tell you how cool it was that he turned out to be the nicest guy. He was so giving and honest."

But some of Grace's most difficult scenes were dialogue-driven ones opposite Michael Douglas, whose character holds Seth accountable for Caroline's addiction. "This is my first film, so you can imagine how nervous I was to be doing scenes with Michael. I can call him 'Michael' now because I've worked with him," laughs Grace. "I can't tell you how cool it was that he turned out to be the nicest guy. He was so giving and honest."

Similarly, the film novice admits, "I wasn't inherently comfortable when I came to the set the first day. But Steven Soderbergh is the funniest guy I think I've ever met in my life. Also, he was totally willing to let me try a lot of things, and I started to realize how loose you could be and how much fun you could have - even with a serious subject matter. Once I got that, I became comfortable."

Ultimately, says Grace, "What I'm really hoping is that just by hanging out with so many brilliant people, by accident some of it will rub off on me!"

Douglas comments, "It was so exciting to see - I wouldn't say 'raw talent,' but both Erika and Topher are so young, and you think of acting as something that improves with age and that's not necessarily true.

"Erika has a tough role and she's a wonderful actress and very powerful. To be truthful, I was expecting to see some wasted young lady come in who'd been there and done it and back again. Quite the contrary: Erika is very anti-drugs, and yet she was able to act the part of somebody who's done it all. As for Topher, he and I have similar backgrounds. We both grew up in Connecticut and went to Eastern prep schools, and he has a dry, self-deprecating sense of humor."

"Erika has a tough role and she's a wonderful actress and very powerful. To be truthful, I was expecting to see some wasted young lady come in who'd been there and done it and back again. Quite the contrary: Erika is very anti-drugs, and yet she was able to act the part of somebody who's done it all. As for Topher, he and I have similar backgrounds. We both grew up in Connecticut and went to Eastern prep schools, and he has a dry, self-deprecating sense of humor."

Douglas adds, "With both of them, I'm really impressed that at such a young age they have such confidence in their own existence, their own presence. Whatever insecurities they might have, they have an inherent sense of honesty."

The third part of Traffic is anchored by the character of Helena Ayala played by Catherine Zeta Jones).

The character of Helena, notes Bickford, "was taken fairly directly from the miniseries. Helena is the wife of a very successful businessman, Carlos Ayala portrayed in the film by Steven Bauer] in San Diego. She has a young son and is pregnant with another child. The Ayala family lives in a beautiful home. She's basically living the American dream. Suddenly, she discovers that their lifestyle has been subsidized by her husband's illegal drug business, and she has to make choices about how to save her family."

The character of Helena, notes Bickford, "was taken fairly directly from the miniseries. Helena is the wife of a very successful businessman, Carlos Ayala portrayed in the film by Steven Bauer] in San Diego. She has a young son and is pregnant with another child. The Ayala family lives in a beautiful home. She's basically living the American dream. Suddenly, she discovers that their lifestyle has been subsidized by her husband's illegal drug business, and she has to make choices about how to save her family."

"The strange thing is," admits Gaghan, "Helena's voice just popped into my head. Long before I started the script I had a dream and in the dream someone was talking - a female voice, saying 'Duck salad - you never eat duck salad!' And it turned out this was the voice of Helena in the dining room of her country club in La Jolla chit-chatting with the other wives."

"Then I thought, what if she was a woman who was very smart but fundamentally naive. She lives in a beautiful house behind a gate and thinks her aristocratic husband comes from old Mexican money. Basically, she does all the right things: she's involved with the right charities, she's an involved, good parent. And then she discovers that all this time she's been living a lie."

"Then I thought, what if she was a woman who was very smart but fundamentally naive. She lives in a beautiful house behind a gate and thinks her aristocratic husband comes from old Mexican money. Basically, she does all the right things: she's involved with the right charities, she's an involved, good parent. And then she discovers that all this time she's been living a lie."

When the role was initially offered to Catherine Zeta Jones, only her family knew her carefully guarded secret. "My predicament, when Steven called me was that I knew I was pregnant," she laughs. "I had never met him personally, but I very much wanted to work with him. I asked when he planned to go into production and all the while I was counting the months in my head, trying to figure out how far along I would be at that time. I finally told him that if we started in April 2000, I would be 5 months pregnant. I also said that I thought being pregnant might be an important aspect for the character of Helena, but if he hated the idea, I would understand."

Bickford remembers, "When we heard that Catherine was pregnant, our first thought was, 'That's fantastic for the story - we couldn't have made that up!' It gives Helena another dimension and motivation for why she makes such a drastic turn."

Zeta-Jones sees Helena as having "probably never been in a room where somebody was doing drugs, and suddenly she is thrown into that world. She is a very social animal, very politically correct in many ways. She contributes to the community, volunteers, hosts charity events, and is a good mother and wife. She lives in a perfect world - until the day DEA agents burst into her home, arrest her husband, and haul him off to jail. When she finds out that this man, who she truly loves, has made his living importing illegal drugs, it is completely devastating."

"Once she gets over the shock, she takes it upon herself to carry on where her husband left off. Although she has been forced to acknowledge that their lifestyle was built on dirty money, she is determined that nobody take that lifestyle - or her children's futures - away."

"Once she gets over the shock, she takes it upon herself to carry on where her husband left off. Although she has been forced to acknowledge that their lifestyle was built on dirty money, she is determined that nobody take that lifestyle - or her children's futures - away."

Along with portraying a pregnant woman, Zeta-Jones was asked by Soderbergh to do something else she had never done before in a film - to speak in her normal voice and accent. She says, "It was very liberating for me because I'd never had a chance to do that. I usually have to hide my real accent. Steven was really adamant that he wanted it to be just the way I speak normally - which adds to the history of the character, I think. You know she's not an American and although her husband has Hispanic roots, he is an American. The feeling is that Helena was a woman who came to the United States, fell in love, and never left."

"There are several reasons why I felt it was a good idea for Catherine to not adopt an accent," Soderbergh notes, "First, I liked the mix of the sound of her voice and having a husband who was Hispanic. These are two people from different ethnic backgrounds who live in the United States, and there are many couples just like that."

"Secondly, I wanted her to be as loose as possible and to not be thinking about an accent - or else she'd be trying to give a performance and at the same time make sure her accent was spot-on. It would always occupy a portion of her brain. I wanted her to feel comfortable, and I think it resulted in a spontaneous quality in her performance."

Zeta-Jones says, "What also really attracted me to this movie was the subject matter of drug trafficking and the people connected with drugs. The script was so beautifully constructed that you really felt like you were on a rollercoaster ride. There are such great characters, and you become interested in each individual story."

Zeta-Jones says, "What also really attracted me to this movie was the subject matter of drug trafficking and the people connected with drugs. The script was so beautifully constructed that you really felt like you were on a rollercoaster ride. There are such great characters, and you become interested in each individual story."

"I loved the fact that there are three stories that largely don't connect physically, but are totally connected in essence. I also liked the way it demonstrated a cross-section of society being affected by drugs. You don't have to come from any particular background or education - you don't have to be down-and-out - to be addicted. The film doesn't just follow a stash of cocaine through the border. You follow the characters involved with getting drugs across the border - or getting drugs for themselves."

Soderbergh comments that "in all these stories, somebody is connected to the world of drugs, whether it's through selling them, using them, or policing them. They are pulled into something that is bigger than they are. That becomes the theme running through each story - the size and scale of it, what a force it is."

Gaghan adds, "There's a cumulative effect of seeing these stories intertwine and cross each other - how drugs come from one place, move around, and end up in other places and the lives they affect along the way. A prep school kid in Ohio ends up using drugs that were moved up by someone in Mexico. And each of the players in this drama has a real life that's worth examining. It doesn't bear over-simplification. It's emotional at every level. Everyone involved in the war on drugs - the consumer, the trafficker, the interdiction forces - has a passionate viewpoint."

Gaghan adds, "There's a cumulative effect of seeing these stories intertwine and cross each other - how drugs come from one place, move around, and end up in other places and the lives they affect along the way. A prep school kid in Ohio ends up using drugs that were moved up by someone in Mexico. And each of the players in this drama has a real life that's worth examining. It doesn't bear over-simplification. It's emotional at every level. Everyone involved in the war on drugs - the consumer, the trafficker, the interdiction forces - has a passionate viewpoint."

"Everybody who read the script - whether from the political right or the left, law enforcement or drug addicts - thought the script took their side."

"I don't know what the last 'big drug movie' was," comments Del Toro. "But Traffic deals with the problem - and it's a big contemporary problem. The realism makes it up-to-date. No one in the film is a perfect hero - everybody's a human being."

Bickford notes, "What was curious about the reaction to the script was that everybody felt that it represented their point of view. The DEA, which gave us enormous support, felt that it was one of the most truthful things they'd ever read about what it's like to be in law enforcement fighting the fight."

Bickford notes, "What was curious about the reaction to the script was that everybody felt that it represented their point of view. The DEA, which gave us enormous support, felt that it was one of the most truthful things they'd ever read about what it's like to be in law enforcement fighting the fight."

"One of the things we've tried hard to do is to make the movie as realistic and gritty as possible. Part of achieving that was using many of the real people involved. We spent a lot of time with the DEA in Washington and San Diego and with agents from EPIC (the El Paso Intelligence Center), where we also were allowed to film. We tried to get their journey right. We filmed at the San Ysidro/San Diego border and the director for the U.S. Customs service agreed to play himself, giving Michael Douglas' character a tour of the actual crossing with real drug busts going on all around us."

"Working in Mexico was really special," remembers Del Toro. "The people were so warm and willing to help. We did scenes on the spot, and the extras were real people."

Soderbergh adds, "The interesting thing about using real people is the contrast between them and an actor. There's a different quality, and with a film like this it's very useful."

"On the border and at EPIC, we had real officials explaining to Michael Douglas' character what they do, what their problems are, and how they feel their jobs could be made easier through funding or publicity."

"On the border and at EPIC, we had real officials explaining to Michael Douglas' character what they do, what their problems are, and how they feel their jobs could be made easier through funding or publicity."

Even more realistic, reveals Soderbergh, is a cocktail party sequence set in Washington, D.C.: "Five U.S. Senators, two Congressmen, a former Massachusetts Governor, a former U.S. Ambassador, and several well-known journalists appear as themselves. They talk to Michael's character about their feelings regarding the drug war, what the problems are in their state, and so forth. Even if you don't recognize who they are, there is a different energy to them and you can tell that they're real. There is no substitute for that. Because Michael is politically astute and a bright guy, he knew what sort of questions to ask, and I simply followed him around with the cameras and asked the person who was talking to him to explain to his character what was going on from their end."

"I actually threw Michael Douglas into these situations. When we were at the border, they were actually busting cars that were filled with drugs and people - right in front us. We filmed the dogs and the agents tearing these cars apart while the experts were explaining to Michael how it worked, how many cars come through, how much dope they bust a month, what happens to the drivers, everything. And it was all improvised, all done documentary-style. Then I'd work in a little bit of the scripted material."

"I actually threw Michael Douglas into these situations. When we were at the border, they were actually busting cars that were filled with drugs and people - right in front us. We filmed the dogs and the agents tearing these cars apart while the experts were explaining to Michael how it worked, how many cars come through, how much dope they bust a month, what happens to the drivers, everything. And it was all improvised, all done documentary-style. Then I'd work in a little bit of the scripted material."

The director admits, "It can be skating on thin ice at times, but if you pull it off and if you create an environment where the actor and the real person feel comfortable, then you end up with something that's entirely different than you would have gotten with two actors."

For his part, Douglas remembers, "My first day of filming was at the border. In the script, I had a few lines - a few questions to ask. When I arrived on the set, Steven introduced me to Rudy M. Camacho, who is the real director of the U.S. Customs Service in San Diego, and said, 'Rudy will take you through and you ask him whatever you want. Now let's go.' So my first scene was an 11-minute take of improvised material! Then we proceeded to the next scene - the entire first day was like that."

"When we were at the El Paso Intelligence Center, he had me sitting down at a table with several people who actually work at EPIC as well as a former DEA agent who used to work there, and we did the same thing."

"When we were at the El Paso Intelligence Center, he had me sitting down at a table with several people who actually work at EPIC as well as a former DEA agent who used to work there, and we did the same thing."

Recalling the shooting of the cocktail party sequence, Douglas states, "I loved it. I so appreciated the confidence that Steven has in his actors, and the excitement and the joy of doing it that way. I like to keep up on current events and think that I'm fairly politically current, so to have an opportunity to talk to these people, in character, on such matters, was a treat. It all works because my character, Robert Wakefield, is not supposed to be an expert."

"At this point in my life talent is important, but working in a pleasant environment with people who are nice is equally important. It says a lot for Steven Soderbergh and how he sets the whole tone on a film that he attracts the interest he does from actors and crew."

"There's a lot of good things about working with Steven: he's fast, clean, and cheap," laughs Del Toro. "He works with a very tight crew. There's no napping on his set, no time in-between set-ups sitting in your trailer like you might on other films."

"But my favorite thing about Steven is that he listens. He really listens to what you have to say, and then he'll think about it and he'll agree or disagree. He'll listen and he'll help you."

Soderbergh says, "I really like actors and I like working with them. I think most of them know the pleasure that comes from enjoying the experience of working on a film. That's all we have at the end of the day. A tape or DVD on the shelf doesn't have any meaning to me. It's those months I've spent with the actors and the crew, so I like to make sure people come away feeling like it was a good thing to have done. I make a real effort to make sure we're all enjoying it. After all, it's a big chunk of my life as well."

Soderbergh says, "I really like actors and I like working with them. I think most of them know the pleasure that comes from enjoying the experience of working on a film. That's all we have at the end of the day. A tape or DVD on the shelf doesn't have any meaning to me. It's those months I've spent with the actors and the crew, so I like to make sure people come away feeling like it was a good thing to have done. I make a real effort to make sure we're all enjoying it. After all, it's a big chunk of my life as well."

On Traffic, the pre-production process (essential to any and every movie) was shortened considerably when Steven Soderbergh decided to serve as the film's cinematographer, a.k.a. the director of photography. (When Soderbergh's request to take the credit "Directed and Photographed by" was rejected by the Writers Guild of America, he opted to take the pseudonym "Peter Andrews" as cinematographer.)

"When I started making short films, I shot my own," notes Soderbergh. "Cinematography has always been an area that I've been interested in. I feel very comfortable with photography. More recently, I shot 'Schizopolis,' and I had worked with some very good cinematographers. Because of the style of Traffic, I felt ready to take on the job."

"To make Traffic, I wanted as lean a unit around the camera as possible, to strip the camera crew down as much as I could. Another reason was that I thought I would have a hard time talking a cinematographer into doing what I had in mind. I wanted three distinct looks for each of the stories. I used a combination of color, filtration, saturation, and contrast so that as soon as we cut to the first image of the next story, you would know that you were in a different place. Then we took the Mexico sequence through an Ektachrome step, which gave it a very gritty, contrasty look."

Soderbergh also operated the camera, which he had also done on several of his other films. The difference on Traffic was that nearly the whole film was shot with the camera hand-held. He comments, "From the beginning, I wanted this film to feel like it was happening in front of you, which demands a certain aesthetic that doesn't feel slick and doesn't feel polished. There is a difference between something that looks caught and something that looks staged. I didn't want it to be self-consciously sloppy or unkempt, but I wanted it to feel like I was chasing it, that I was finding it as it happened. On the other hand, I didn't want to give people a headache."

Soderbergh also operated the camera, which he had also done on several of his other films. The difference on Traffic was that nearly the whole film was shot with the camera hand-held. He comments, "From the beginning, I wanted this film to feel like it was happening in front of you, which demands a certain aesthetic that doesn't feel slick and doesn't feel polished. There is a difference between something that looks caught and something that looks staged. I didn't want it to be self-consciously sloppy or unkempt, but I wanted it to feel like I was chasing it, that I was finding it as it happened. On the other hand, I didn't want to give people a headache."

"One of the things I like about operating the camera is that you have a stronger sense of what you're getting. The disquieting thing about some of the techniques we were employing on this film was that sometimes what I was seeing through the camera lens bore no relation to what I was going to see on the print - and that was a little scary. Essentially I was flying on instruments, like a pilot. I'd know what my back light was and my front light and that there was a filter and that I was 'flashing' the film. I knew that based on the numbers, it should be fine. But I'd look through the lens and not see anything. I just had to hold my breath and believe. Then the next day the dailies would come in, and the image would be there. It was a little disorienting."

Soderbergh also made the choice to film using only available light - whenever possible. But, he remembers that was not always the case: "When we were prepping and going on tech scouts, we had lots of conversations about using natural light. So it was a pretty funny moment the first day of production, when we showed up at the first location and the light was not great. Sure enough, we had to haul the 18-K light off the truck. I thought, 'Oh-oh, here we go.'"

"It's really about creating the feel that you just showed up and shot. There is an art to creating that feeling artificially. For example, in the Mexico sequences, we manipulated the film with filters and shutter angles which resulted in our shooting at a much slower speed than would normally be the case. And that meant hauling out some lights."

"It's really about creating the feel that you just showed up and shot. There is an art to creating that feeling artificially. For example, in the Mexico sequences, we manipulated the film with filters and shutter angles which resulted in our shooting at a much slower speed than would normally be the case. And that meant hauling out some lights."

He laughs, "There were days when, if the DP were not me and had been doing what I was doing, he would have had a heart attack. It didn't happen often, but sometimes I'd get two-thirds of the way through a lighting setup and it wasn't what I had in my mind's eye. I'd turn to Jim Plannette, the gaffer, and say, 'Tear it down. It isn't right, we're doing something wrong.' But because I was DP'ing and operating, we moved very quickly so we had the time to do that when we needed to. It's also a real benefit for the actors, to be working quickly."

"I told Michael Douglas when we met that he would spend more of his day acting on this movie than any movie he'd ever been on - and he did. Because we moved really fast, the actors were not waiting around. That meant they could stay connected to their characters all day. What I also discovered is that it was relentless for me, too: there was no five-minute break while the cinematographer was setting up for me. From the moment I showed up until the moment I left, I could not leave to do anything, because I was solely responsible for the rhythm of the shoot."

Of that fast pace, Soderbergh notes, "I feel that what you want to do is get into that space where you're going totally on instinct. You aren't agonizing over everything. That energy is more important than perfection. Perfection is boring: what's exciting is something that is alive. And things that are alive have flaws. I'm all for the accident that happens on-camera."

Of that fast pace, Soderbergh notes, "I feel that what you want to do is get into that space where you're going totally on instinct. You aren't agonizing over everything. That energy is more important than perfection. Perfection is boring: what's exciting is something that is alive. And things that are alive have flaws. I'm all for the accident that happens on-camera."

Being a filmmaker as well as an actor, Michael Douglas "totally understood my situation," comments Soderbergh. "I try to be empathetic to the actor and have a sense of what it's like for them to be on the other side of the camera. I don't expect them to think about what I have to deal with because it's not really their job. But Michael does it reflexively, because he's been on the other side. So he understood when I'd say I needed to come up with something different, or needed some more time, or had to redo something because it wasn't quite the way I wanted it. That was a real luxury for me."

Michael Douglas responds, "Steven is truly a one-man band. If you think of movies as losing a little piece of yourself, this man lives off of film. He's as close as we have to an auteur. Also, he's just so fast. For actors, depending on how you like to work - it's a blessing."

"Steven has an easy manner, and his choice of lenses allows him to stay a little further away from the actors - so you don't have the feeling of a camera interrupting or being in your face. There is an acting boundary that is always abused by directors who put lights and cameras and reflectors in the way. Steven gives you an environment that allows you to carry on a conversation with fairly good concentration. You don't have to worry about it like you do with directors who have the camera and an operator hanging right over your shoulder."

"Steven has an easy manner, and his choice of lenses allows him to stay a little further away from the actors - so you don't have the feeling of a camera interrupting or being in your face. There is an acting boundary that is always abused by directors who put lights and cameras and reflectors in the way. Steven gives you an environment that allows you to carry on a conversation with fairly good concentration. You don't have to worry about it like you do with directors who have the camera and an operator hanging right over your shoulder."

Sodberbergh admits, "I tend to not like having the camera too close to the actor. If I want to be close, then I'll go to a longer lens. That accomplishes a couple of things: first, it gives the actor more space and helps him forget that there are cameras around, which is always a good thing. And I think also, subconsciously, for the audience, it helps create the impression that there just happened to be a camera shooting what they are watching. When you step back a little and use a longer lens, that sense of documentary is amplified a bit."

"Hopefully, ten minutes into Traffic people will totally forget that the camera was hand-held. Unless there is a very specific movement or activity going on in the scene, the camera is not running around the room. Sometimes when I was shooting there would be a shake or a focus problem or a weird cut, and I'd feel, 'That's perfect.' Because it keeps the feeling that this wasn't labored over to death. The audience will feel, 'God, anything could happen.' Even on Erin Brockovich (2000) or Limey, The (1999) or Out Of Sight (1998), when I had a set shot, instead of putting the camera on a tripod, I'd put a sandbag on the tripod instead of a head and put the camera on top knowing that the sandbag would keep it from being perfect - that there would be something slightly not quite nailed down about it. That's the sensation I want - sort of controlled anarchy."

"Hopefully, ten minutes into Traffic people will totally forget that the camera was hand-held. Unless there is a very specific movement or activity going on in the scene, the camera is not running around the room. Sometimes when I was shooting there would be a shake or a focus problem or a weird cut, and I'd feel, 'That's perfect.' Because it keeps the feeling that this wasn't labored over to death. The audience will feel, 'God, anything could happen.' Even on Erin Brockovich (2000) or Limey, The (1999) or Out Of Sight (1998), when I had a set shot, instead of putting the camera on a tripod, I'd put a sandbag on the tripod instead of a head and put the camera on top knowing that the sandbag would keep it from being perfect - that there would be something slightly not quite nailed down about it. That's the sensation I want - sort of controlled anarchy."

Another way to keep Traffic feeling to audiences as though it were happening in front of them was to take the production to locales where the film's stories take place. The film began production in April with four weeks of shooting in San Diego. The company then hit the road, traveling to the border town of Nogales, Mexico; a desert airstrip in Las Cruces, New Mexico; EPIC headquarters in El Paso, Texas; government buildings in Columbus, Ohio and a variety of neighborhoods in Cincinnati, Ohio; a Georgetown mansion and The White House in Washington, D.C.; and, finally, Los Angeles.

"Shooting on practical locations is part and parcel with trying to create the feeling for the audience that it is happening in front of them," relates Soderbergh. "There are things that can go wrong, but more often than not you get things that you wouldn't if you were filming on a stage or trying to fake the location. We had a couple of intensive days in the desert and in the West End of Cincinnati, and I feel it was worth it. You can't buy that, you have to go and get it. Part of the appeal of Traffic is the contrast between the different worlds that each character inhabits."

"Shooting on practical locations is part and parcel with trying to create the feeling for the audience that it is happening in front of them," relates Soderbergh. "There are things that can go wrong, but more often than not you get things that you wouldn't if you were filming on a stage or trying to fake the location. We had a couple of intensive days in the desert and in the West End of Cincinnati, and I feel it was worth it. You can't buy that, you have to go and get it. Part of the appeal of Traffic is the contrast between the different worlds that each character inhabits."

"For me, the most fun on any movie is when something unanticipated happens that's better than what you imagined. That's what you live for, and if you get a couple of those days, then you're living right. You try and create an environment in which those things can happen. It means having your antennae up all the time."

Helping Soderbergh to create that environment, from pre-production on, were Traffic production designer Philip J. Messina (previously Soderbergh's production designer on Erin Brockovich (2000) and art director on Out Of Sight (1998)) and costume designer Louise Frogley (previously Soderbergh's costume designer on Limey, The (1999)).

Messina and location manager Ken Lavet scoured the United States in order to come up with the many locations for the film. In all, the production filmed at over 100 locations. Messina's prior collaborations with Soderbergh had shot, respectively, almost entirely on practical locations (Erin Brockovich (2000)) and filmed in four distinct cities (Out Of Sight (1998)).

Messina and location manager Ken Lavet scoured the United States in order to come up with the many locations for the film. In all, the production filmed at over 100 locations. Messina's prior collaborations with Soderbergh had shot, respectively, almost entirely on practical locations (Erin Brockovich (2000)) and filmed in four distinct cities (Out Of Sight (1998)).

"Philip J. Messina is one of the least dogmatic designers I've ever met," says Soderbergh. "He absolutely puts the movie first. He wants everything to look right, but he also knows what it is I have to deal with and he knows the practical limitations of shooting on location. It means that sometimes you have to make certain compromises. He understands that there are often very simple and elegant ways to turn something from the ordinary into above-the-ordinary. If I come in and say, 'This set is basically right but it's missing a little something,' then when I come back he'll have done exactly what was needed. A real testament to Phil's work is that, after he's redone a practical location, the owners have decided to leave it the way he did it. That actually happens a lot, so he must be doing something right!"

Messina feels, "Basically, my job is to give the director what he wants. You create a situation where he can focus on the things he wants to focus on. We knew that Steven wanted to approach this film in a non-conventional way and also that we were going to move fast, which presented challenges."

"Because the film was so location-driven, there was a lot of room for serendipity. Personally, I took a different creative approach and tried to open myself up to the possibilities that were being presented where we were, because that's the way Steven was approaching Traffic. He would arrive at the set and select his shot from the conditions that are presented to him. I tried to take the same approach to the way I designed the sets, and found it very liberating. It was different from the way I usually work and the way you're trained to work as an art director and production designer. It was extremely complex - and a lot of fun."

"Because the film was so location-driven, there was a lot of room for serendipity. Personally, I took a different creative approach and tried to open myself up to the possibilities that were being presented where we were, because that's the way Steven was approaching Traffic. He would arrive at the set and select his shot from the conditions that are presented to him. I tried to take the same approach to the way I designed the sets, and found it very liberating. It was different from the way I usually work and the way you're trained to work as an art director and production designer. It was extremely complex - and a lot of fun."

"Traffic has a much more stylized approach to the design than Erin Brockovich (2000) did," comments Messina. "Out of necessity, that film had a very realistic documentary-style approach with real people living in real homes - no need to stylize the look. The settings of our stories in Traffic - dive hotels, crack dens, drug labs, and four mansions in different parts of the country - afforded a juxtaposition between highs and lows."

Messina elaborates, "With the different elements in each city, we started making connections to try and thread it all together. Steven gave a very specific cinematic look to each location: In San Diego, he used a film processing technique called 'flashing.' In the desert, he changed the shutter angles and used a tobacco filter. In Cincinnati, he used a blue filter."

Messina elaborates, "With the different elements in each city, we started making connections to try and thread it all together. Steven gave a very specific cinematic look to each location: In San Diego, he used a film processing technique called 'flashing.' In the desert, he changed the shutter angles and used a tobacco filter. In Cincinnati, he used a blue filter."

"The locations were mainly chosen for how well and how easy they would be to light. While we were still scouting, we even noted specifically where the light was going to be at certain times of the day. If it was a room, we noted where the windows were and how we would decorate that area based on the light source. Throughout the shoot, I used a lot of reflective surfaces. With the strong light sources, reflective pieces make the environment come alive, so there are lots of mirrored surfaces and gold and brass accents. Also, the way Steven was moving the camera, you catch glares off of tables and decorative pieces and it ends up being interesting to look at."

As an example of the latter, Messina cites "the scene where the two DEA agents Montel Gordon and Ray Castro, portrayed by Don Cheadle and Luis Guzman are waiting with Eduardo Ruiz played by Miguel Ferrer to testify, they're in a San Diego courthouse anteroom which had one direct light source, a huge window. There was a very large conference table with a glass top. If you stood in the corner looking towards the window, the glass top became a mirror. The way Steven shot it, the trio was sitting at the table in a kind of tableau. The mirrored table basically reflected and gave double images of all of them."

As an example of the latter, Messina cites "the scene where the two DEA agents Montel Gordon and Ray Castro, portrayed by Don Cheadle and Luis Guzman are waiting with Eduardo Ruiz played by Miguel Ferrer to testify, they're in a San Diego courthouse anteroom which had one direct light source, a huge window. There was a very large conference table with a glass top. If you stood in the corner looking towards the window, the glass top became a mirror. The way Steven shot it, the trio was sitting at the table in a kind of tableau. The mirrored table basically reflected and gave double images of all of them."

"Because of the complexity of the script, and how when the film was cut together everything was going to be interwoven, we selected locations that constantly communicated the cities we were in. The challenge was to select locations that had not just a distinct palette but a certain look, so when you came back to this place after you'd been to another city in the film, you'd know where you were."

Messina notes, "My job was to give a coherent look to each city and environment. San Diego was more sedate: we used cleaner lines and stayed away from Spanish architecture. In Mexico, there was a lot of texture, and it was almost chaotic, especially for the exterior street scenes in Nogales."

"The great thing about the way the script was constructed is that I got to establish people in their own environment and then take them out of it - which is what the story is about, in a way. The characters don't just stay in their environments, they cross over into different cities. Helena goes from her country club luncheons to the streets of Tijuana; Robert Wakefield goes from Washington, D.C. to the border, among other examples. One particular visual treat is the juxtaposition of seeing Javier in the desert busting smugglers, then in the hubbub of his favorite streetside taco stand, and then in the pool at the San Diego Marriott."

"The great thing about the way the script was constructed is that I got to establish people in their own environment and then take them out of it - which is what the story is about, in a way. The characters don't just stay in their environments, they cross over into different cities. Helena goes from her country club luncheons to the streets of Tijuana; Robert Wakefield goes from Washington, D.C. to the border, among other examples. One particular visual treat is the juxtaposition of seeing Javier in the desert busting smugglers, then in the hubbub of his favorite streetside taco stand, and then in the pool at the San Diego Marriott."

Messina also enjoyed designing The Fun Zone, the film's fictional restaurant that caters to children but is also the setting for criminal adult activity. Accordingly, he notes, "We took an empty restaurant and nearly made it one of the levels of Dante's Inferno. There are very bright primary colors and strobing lights and reflective surfaces. It's supposed to be disorienting when Ray and Montel chase Ruiz through the parking lot and into this darkened area. Later in the movie, Helena, under the guise of taking her son to the restaurant, arranges to meet a connection there."

Among other key locations that stand out from the shoot for Messina was Perennial Storage, "the public storage facility where we first meet Ruiz, because it was like a rat's maze with all the bright orange on the garage doors. I loved the way that looked on film."

He also favored the Mexican military base where General Salazar (portrayed by Tomas Milian) has his headquarters. The buildings are located in Socorro, Texas, on the outskirts of El Paso; and, known as the Rio Vista Farm Historic District, were recently nominated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. So, Messina remembers that "half of the place had been renovated and half was in disrepair. We ended up covering some of the recently repaired roofs with rubble and torn asphalt roofing paper. We actually had to refurbish it back down to a level of disrepair."

He also favored the Mexican military base where General Salazar (portrayed by Tomas Milian) has his headquarters. The buildings are located in Socorro, Texas, on the outskirts of El Paso; and, known as the Rio Vista Farm Historic District, were recently nominated for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. So, Messina remembers that "half of the place had been renovated and half was in disrepair. We ended up covering some of the recently repaired roofs with rubble and torn asphalt roofing paper. We actually had to refurbish it back down to a level of disrepair."